This text is a short version of the keynote I held at Pro Quote Film’s “Family-friendly filming – the concrete congress” on 21.2.23. My first text on this topic was published on 14.4 2014 under the title “Children, cinema, career: how family-friendly is the film industry?”

Belinde Ruth Stieve at Pro Quote Film’s “Family-friendly filming. The concrete congress!”. Photo Sibylle Anneck

Family-Friendliness and the Film Industry

Background

Families are very popular in the film and television industry – as an audience, as a target group. But this family-friendliness is not what we are talking about here, but the compatibility of family and professional career in front of or behind the camera.

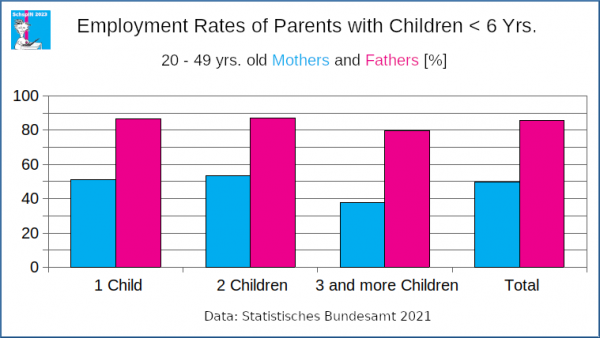

The employment rate of parents with children under six in Germany shows that fathers work 80-90% of the time, regardless of whether they have one, two or three children under six. Only every second mother is gainfully employed in the same family situation.

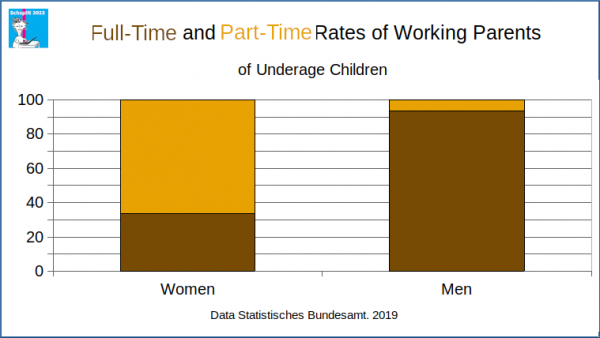

Of working women with minor children, i.e. children under the age of 18, the majority work part-time, regardless of whether they want to or have to. Only 5 % of men with minor children work part-time.

In a recent study (Jörg Langer 2022), 43 % of the filmmakers surveyed said they had children and were single parents or in a relationship. At the same time, more than two thirds of the respondents (79 %) said that it was difficult or impossible to reconcile a film career and a family.

Mind you, family-friendliness is not just about parents of young or middle-aged children, but also about people who care for elderly relatives, or whose partner is seriously ill, and who want to stay connected to the film industry.

Best Practice

From Denmark we hear about best practice. They have the eight-hour working day that the big production companies and broadcasters have committed to. Not eight hours of camera time like we have and a total of a twelve-hour day, which is also overrun more often than not. And yet they shoot their projects in comparable shooting periods as we do. Then there are projects, for example, where the people in charge said: We’re shooting away from home, everyone wants to be with their children at the weekend, so we’ll make the shooting days longer and only shoot for four days.

What other options are there for parents in the film industry?

- You can do it like Jacinda Ardern, whose partner took over childcare.

- Or like Birgitte Nyborg from the Danish series BORGEN. When her teenage daughter became mentally ill, she took temporary leave from her job as head of government.

- The third solution is a paid nanny during production.

Mary Cassatt: Nurse Reading to a Little Girl. 1895. Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

This is mainly provided for female directors and leading actresses. There is a retreat on the set where they can nurse their child in peace or pump milk. The nanny is also present on out-of-town shoots, her flight is paid for, her accommodation, her food. Only the mother pays the salary herself.

But not every mother does. There is no such thing for the assistant director, the sound angler, the make-up artist with an infant or small child. And you don’t want to cast an actress who is not playing the lead role as soon as she is pregnant, because that might cause problems with the insurance.

The thing with money

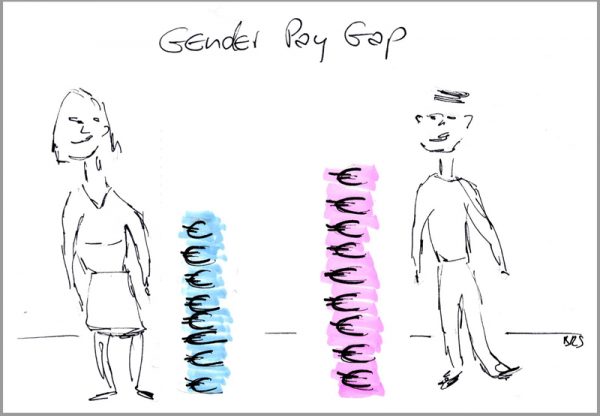

Unfortunately, women also earn less than men in the film industry; estimates put the gender pay gap at at least 30 %. But it can quickly be larger, in individual trades or individually.

In mid-February, a landmark ruling by the German Federal Labour Court stated that equal pay should not depend on negotiating skills and that work of equal value must be paid equally. This should have triggered discussions in the film industry. But they failed to materialise.

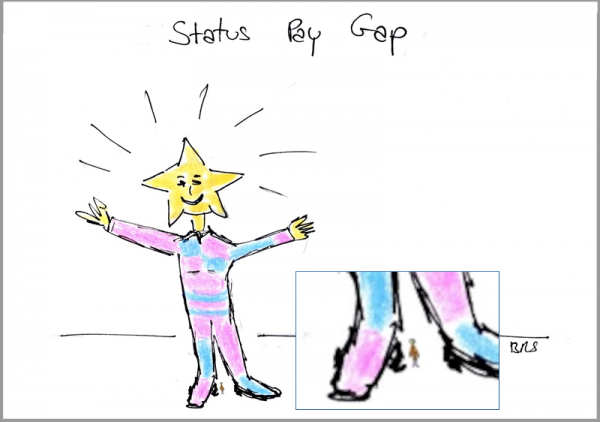

Instead, in addition to the gender pay gap, we also have the status pay gap, e.g. in acting.

This means that the leading roles earn disproportionately more than their colleagues with smaller roles. Market value and negotiating skills, more visibility, more film awards – where, of course, women are again at a disadvantage because there are far fewer roles for them.

Perhaps scale fees with minimum and upper limits are an approach?

What we have at the moment, for example, with TV films, is that the male lead often earns significantly more than the male director, who in turn gets more than the female director, and the female lead still gets a lot based on the whole production time, but significantly less than the male lead.

There are the larger supporting roles and then the smaller ones with one, two, three shooting days. They often say, unfortunately we don’t have much money because the leading roles cost so much, can you work for less than usual? Very few people refuse.

To what extent is that important for childcare? First of all, the actress of small roles has less money. And secondly, she wants to keep in touch with the industry even when she has children or is caring for them. She wants to continue to be seen, and that should work well in our industry, because you don’t have a permanent job there, but individual projects with sometimes more and sometimes less shooting days. But when the salaries are so low and go entirely to childcare, that doesn’t work, of course.

Then there is the problem of blocking days. In Britain, a leading role is not allowed to shoot several productions at the same time. In our country she can. She can even have projects postponed because she has taken on something else.

The supporting roles who are signed up for one, two or three days of shooting have to be available for the whole period and may not find outshortly before shooting starts whether they have the role or not. So no one can plan, no childcare, no provision for

No childcare, no care for schoolchildren, no substitute care for relatives if a whole month has to be kept free for one, two, three days – possibly in another city. That’s why it would help a lot if the main roles had to be completely available for filming, and the big and small supporting roles were allowed to have blocking periods.

At the moment, these can quickly be a reason for exclusion from the cast.

Part-time and job sharing

Part-time work comes in the variant of working fewer hours a day, or fewer days a week.

Let’s take the camera department for a cinema film as an example, there is a DoP, i.e. a cameraman or camerawoman. Then there are the first and second assistant cameramen.

Many people are often named for these positions because they have partly filled in, as a substitute or in addition. We also know this from make-up or sound, from many areas. From there, it’s not so far to job sharing, where two filmmakers share a position, not necessarily on one day, but spread over the shooting time, which doesn’t have to be 50:50, and is already practised in some cases.

Job sharing in front of the camera may be familiar to older people from the US series DALLAS. The role of Miss Ellie was played by two actresses (Barbara Bel Geddes and Donna Reed). No one noticed. Here in Germany there was also that, e.g. in LANG LEBE DIE KÖNIGIN! that also worked.

One obstacle to job sharing for German filmmakers, however, can be European co-productions that are shot abroad. A model like “I only go on set for individual days” is no longer so easy. In addition, a large part of the crew is booked locally for foreign shoots because the fees are lower and there are additional tax advantages. Unfortunately, for reasons of cost, (smaller) supporting roles are often cast locally, the shoot is then bilingual and there is post-synchronisation.

But of course that means that these small roles, this keeping in touch with the industry, is then not possible. A small role would be ideal for me, I care for a relative, I have a child, my partner is ill, but I could take on a small role, earn money, work, be visible. Only it doesn’t work out when this small role is filled on the spot. It is just as difficult for the camerawoman who wants to work part-time.

Trying out new ways

What about a model project? That would be a film production, cinema or television, wherever you say, behind the camera we offer job sharing. We explicitly say, come to us if you want to start slowly again, if you have children, if you have cared for someone or are still doing so. We will try to make everything possible. We are the model project, a professional film production, and we care about compatibility, about job sharing behind the camera.

And in front of the camera, we say, okay, this character is a receptionist, a doctor’s assistant, for example. She is already written into the script as a job-hardened character, and she is then also cast accordingly by two actresses. And then we have the topic of job sharing in the series or in the film, which is great, and we make it possible for two actresses to work in the same way. The software that you use to create shooting schedules can do a lot, and you can enter exactly these parameters for the short working hours, so these few days that are close together, if that’s what you want, or far apart, always on a Monday or something, you can try everything. If that’s what we want.

This model project would have pay transparency, it would publish what everyone earns. The moment people talk about it, Sweden shows that there are no longer such big differences, because would you like to make them public? No, then I’d rather pay everyone the same or comparable.

Corona has brought impulses, namely we have started to question the culture of presence. A lot of things were suddenly done digitally or from home, where before it was “you have to come to the production company or the broadcaster”. Not only but of course also castings or interviews for the crew.

In Germany, a lot is done through laws, through regulations. So a social shooting pass would be one way. You could say that if you want funding, you have to work in a family-friendly way, offer job-sharing opportunities, options like the four-day week and flexible working hours, and so on.

We can also change things by intervening, by asking questions, by saying no, by showing solidarity. We no longer only have leverage in negotiating our own salaries, but also in the framework conditions under which we work together – we always say we are the big film family, don’t we?

If I play the lead role and learn about low special salaries for colleagues, I can say, no, I won’t play under these conditions. If I, as a director, have the opportunity to take my child to the set with breastfeeding and childcare, and then find out that the make-up artist can’t do it, I can say, no, I’m sorry, I don’t want to work like that.

Solidarity and transparency, talking to each other and noticing what others need, not just myself. That is the key.