Who do we listen to on the Radio?

Some time ago, in the early days of my analytical work, I analysed radio programmes from time to time. One programme called ‘Arrested by the police – and then what?’ in the public broadcasting children’s programme Kakadu from 2.11.13 caught my attention, you can read about it here: Tis Early Practice Only… . From 2013 to 15, I also analyzed the radio feature IM GESPRÄCH (In Conversation), which is broadcast on Saturdays from 9 to 11 a.m. on public radio Deutschlandfunk Kultur. If you don’t know the programme, it’s DLF’s main programme with audience participation. There is a presenter and one or two experts who discuss a topic and the audience is involved by phone call or email contribution. I noticed that a lot of male and very few female experts were invited. I’ve written four articles about this so far:

In the first year I wrote to the editors of the programme about it. It’s not a problem if there are all-male programmes, but again and again? DKultur said at the time about its choice of guests:

“We don’t keep any statistics on the gender of the studio guests we invite to our Saturday programme “Radiofeuilleton im Gespräch”. The interviewees are selected on the basis of their expertise in the respective topic; gender parity or quotas play just as little a role as they do for the listeners who speak on the programme.”

If the gender of the guests didn’t matter, why was there such a clear male preponderance?

A talk in Cologne

Last week I was invited to give a keynote speech at the Founders Talk, an event organised by the Mediengründerzentrum NRW (but it was all in German). My topic was From the Fringe to Key Positions – Women in the Media Industry. And since I didn’t just want to talk about film and television, I once again checked the radio programme and its guest lists.

Belinde Ruth Stieve at the Founders Talk from MGZ NRW. Photo Hojabr Riahi

Good news from DLF Kultur Radiofeuilleton IM GESPRÄCH.

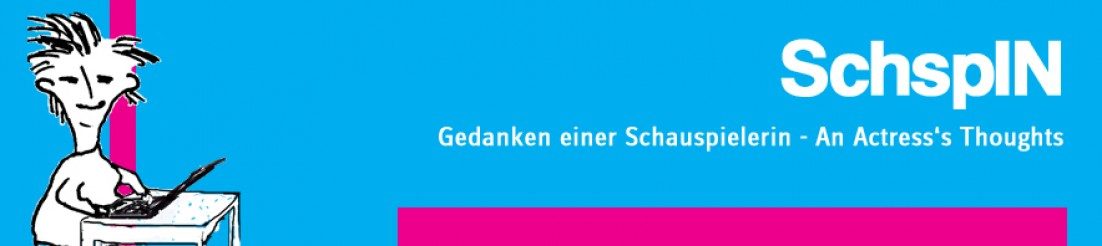

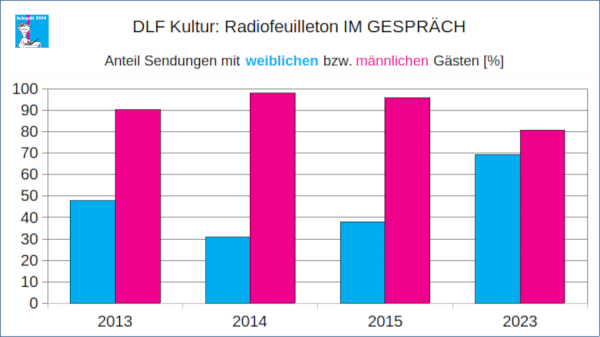

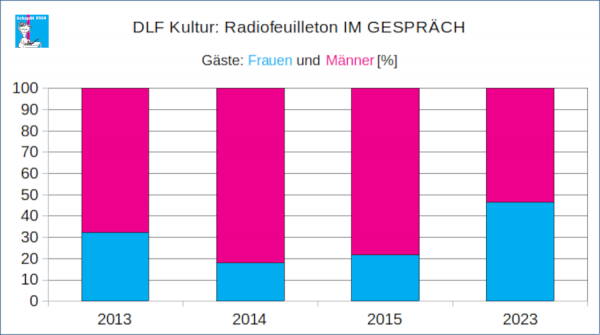

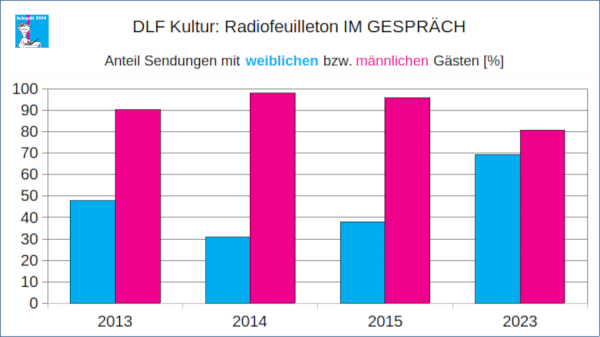

As you can see from the following diagram: the proportion of female experts in the programme is more than 40 % in 2023! Strictly speaking, it is even 46.4 %.

That’s a huge leap if we compare it with the years 2013 to 2015. Great. What happened? Has the editorial team started to consciously counteract the traditional male bias? Have they started “statistics on the gender of the studio guests”? Does gender parity now play a role? Or how did this major change come about?

I don’t know. And the editors of the programme have not yet responded to my questions and follow-up questions. If they do, I will of course add it here.

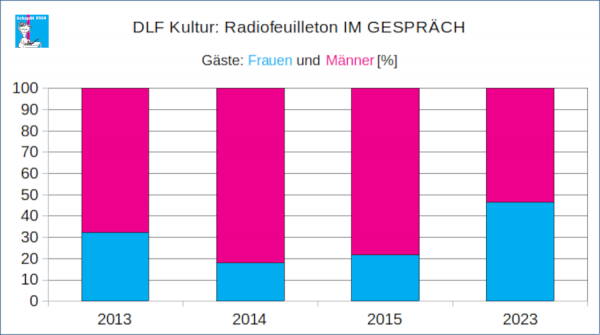

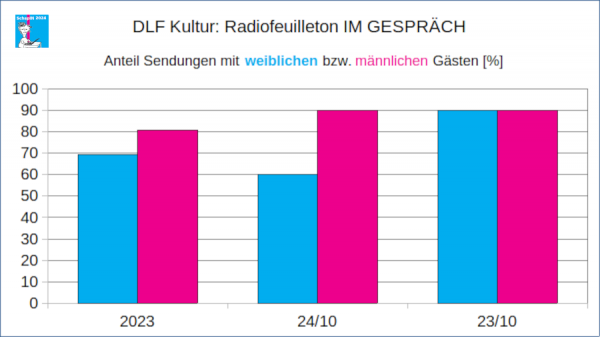

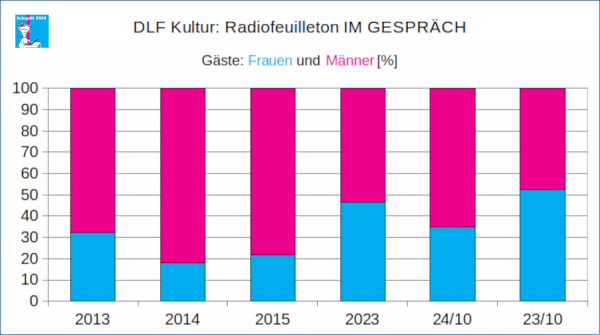

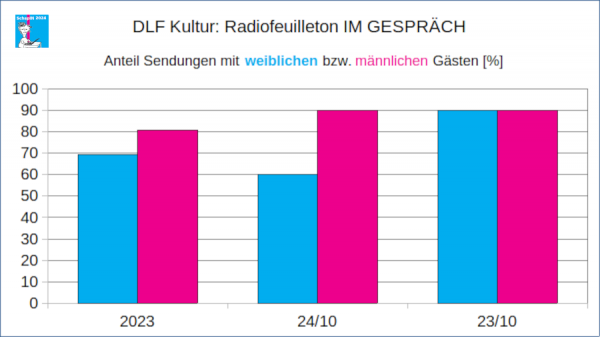

Will the positive trend actually continue in the not-so-new year 2024? Hm, it doesn’t look like that at the moment. The next diagram shows the female–male guest shares for the first ten programmes in 2024 (35 : 65) – and as a comparison for the same period in 2023 (52.6 : 47.4). This year has not started so well:

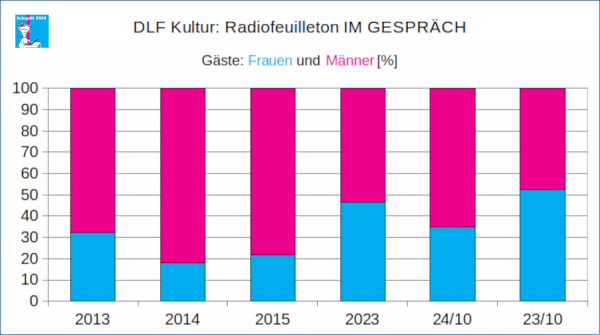

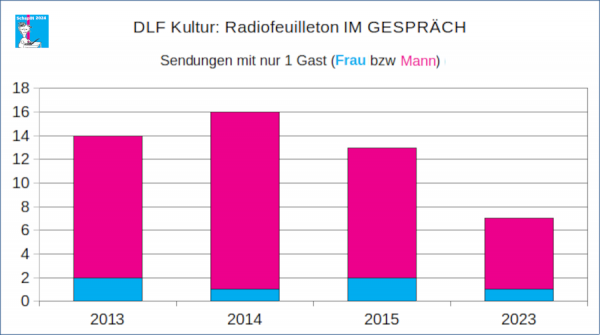

Until I get an answer from the editors, I can only speculate. So for example, let’s take a look at the programmes with just one guest. Most of the time, this single guest was a man.

Could we conclude from this that the “empty guest chairs” were gradually filled with female experts? Probably. But only partially. Because in 2023, there were still seven programmes with just one guest, six of which were men and one of which was a woman.

A bold hypothesis – which I cannot verify as long as the programme team does not contact me – would be that there is also a Covid side effect. In the sense that fewer guests came to the Berlin studio and more guests may have joined the Saturday programme from home or their offices. So it was easier to book two guests for one programme. Basically, I could record this statistically, I would ‘only’ have to listen to all 200 podcasts of the 2013 to 15 and 2023 programmes, at least the first ten minutes in which the guests are introduced, usually with the addition “joined by phone” or “from the Essen studio” or “opposite me” or something like that. Well, that’s a task for another day. Here is an overview of the guest numbers for the four years:

|

Programmes |

Guests |

Guests / Programme |

| 2013 |

52 |

90 |

1,7 |

| 2014 |

52 |

88 |

1,7 |

| 2015 |

50 |

87 |

1,7 |

| 2023 |

52 |

97 |

1,9 |

In 2013-15, there was an average of 1.7 guests in a programme, rising to 1.9 in 2023. But okay, drawing grand conclusions from four years is as risky as claiming that my analyses, articles and emails ten years ago led to the editorial team taking measures for more balanced guest lists. So let’s not go there.

Instead, here are two figures showing the proportions of women and men among the experts for all programmes in the four years. For orientation: both columns of a year do not have to add up to 100%, but the aim should be to achieve similar proportions. Take the figures for 2014: there were female experts in only a third of all programmes, whereas male experts spoke into microphones in almost all programmes. And yes, that does matter. Because when we hear men speaking on every topic and only very rarely women, it does something to us. Some will consider women to be less competent or less broadly positioned as a whole. And see men as the ones who know their stuff and always have something to say.

A public broadcaster, a programme presumably financed with taxpayers’ money, has a particular responsibility in this respect (although I don’t even know whether the guests receive a fee, but that’s another topic).

The next image shows that in 2023 the proportion of women and men among the guests was almost equal – this in contrast to 2013-15. Male participation had its lowest value in 2023 at 80.8% and its highest value in 2014 at 98.1%. Female participation ranges from 38.4% (2014) to 69.2% (2023). This should give the editorial team something to think about:

Here, too, is the data for the first ten programmes in 2024 and 2023, which last year reached 90% of both female and male experts. I think it’s good that the figure isn’t 100, because it’s perfectly fine for there to be programmes in which only some or only others have their say. But this year the two column tops are far apart, separated by 30 percentage points:

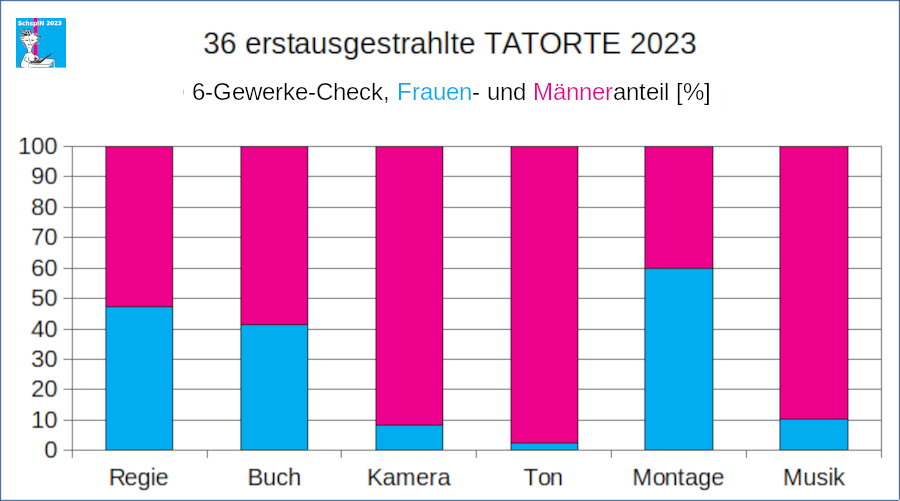

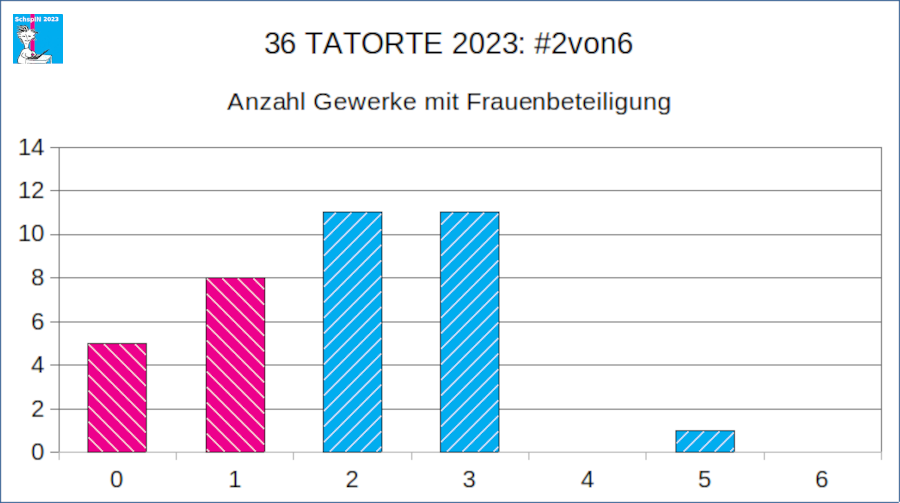

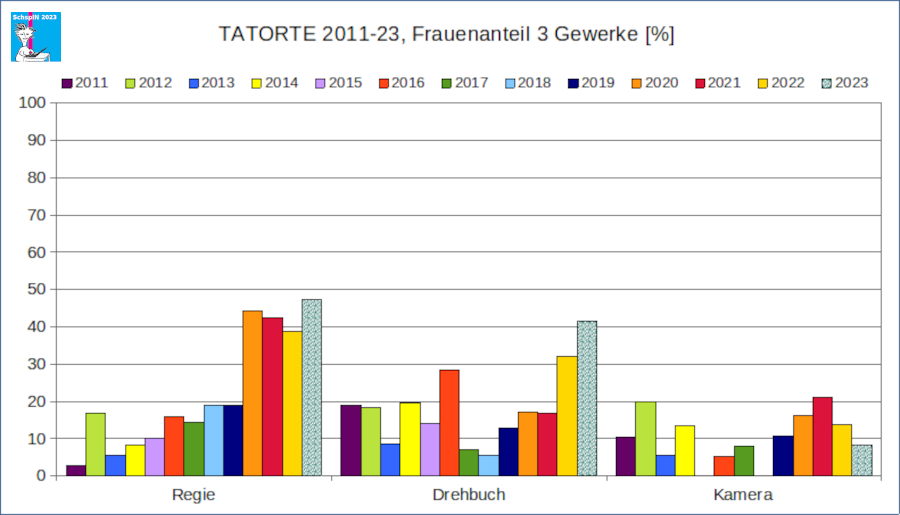

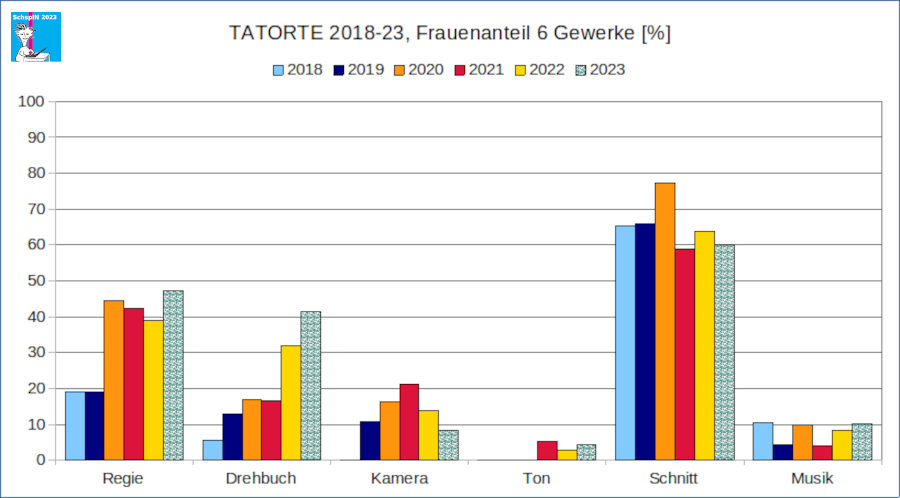

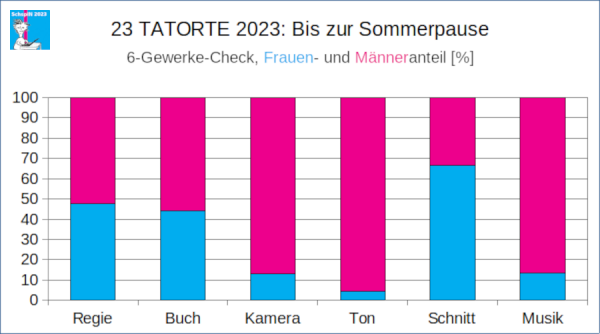

This shows what we’ve already seen, 2024 is off to a really bad start. Will the rest of the year be better? I’m afraid not, 2024 won’t come close to the 2023 final result. It’s just a feeling, but I know this from many studies, for example the 6-departments-checks for the tiresome TATORT: the proportion of women in the vast majority of departments analyzed decreases over the course of a year, and in the first half of the year it is usually clearly higher than at the end of the year.

And what were the Topics?

Listing all the topics that were discussed in the 52 programmes last year, as well as all the topics that perhaps surprisingly didn’t make it into this Saturday format, is beyond the scope of today’s article. Instead, I have compared all the programmes that had only female experts or only male experts at the microphone and see stereotypes here and diversity there. Stereotypes regarding the topics to which only women were invited and thematic diversity in the programmes with experts:

IN CONVERSATION, female guests only 2023:

- Book tips. The power of poetry.

- Adoption. How to foster children. Entitlement to a daycare place. Parent-child relationship. Inheritance without dispute. Clearing out the family home.

- Loneliness.

- A new start.

Male guests only:

- Health checks. Sport for children. Smoking. Back pain. Corona, flu & Co.

- Driving at old age.

- Living sustainability. Energy guzzler internet. Energy transition from below. Rubbish.

- Online fraud. Digital payment.

- Proverbs. How does music touch people?

- 4-day working week.

- The radio CEO talking to listeners.

Who presented the Programmes?

Yes, I also recorded the data on this, both in the past and present. But that too – perhaps in connection with the topics – is something for another day. Maybe by then I’ll have received an answer from the editorial team and learnt how the moderators are involved in finding topics and inviting guests. Who knows.

On a side note: I recently heard German actor and singer Tom Schilling on the weekday version of IM GESPRÄCH – the programme only lasts an hour and there is only one guest at a time, without audience participation. I noticed that he only ever talked about male directors, male actor colleagues and male musicians and male band members and I waited for the presenter Britta Bürger to ask if he didn’t (or did also) work with women. But she didn’t ask. Hadn’t she even noticed?

Concluding Remarks

In 2023, the majority of DLF IM GESPRÄCH Saturday programmes had two guests, and of these a majority had one man and one woman. The proportion of women among the 97 experts in 52 programmes was 46.4 %. Just under 70 % of all programmes had women as guests, a good 80 % men. Compared to the very male-dominated programmes in 2013, 14 and 15, these are encouraging changes. Only the programmes with only female or only male experts are questionable; two female experts or one female expert alone were predominantly booked for children and parenting topics, whereas the programmes with one or two male experts show a much greater variety overall, from health, environmental and digitalisation topics to the 4-day working week.

Listening tips (with me)

Since today’s text is about Deutschlandradio Kultur, here is a reference to three contributions in which I was involved as a guest (speaking German):

I described here how the first interview came about here, the starting point was a programme on political books without any women writers. And a subsequent call from Tarik Ahmia from DLF’s Background Culture and Politics editorial team, who accompanied the preparation and recording of my commentary. Many thanks to him (and of course Gesa Ufer and Max Oppel) for their interest in my side project.