NDR prime-time Cop Dramas

I was invited to do a study of NDR crime films for the current newsletter of the Film & Medienbüro Niedersachsen. With kind permission, here is a translation of the article (pp. 25-27).

The share of women in crews and casts is well below 50%

In early May, NDR (Norddeutscher Rundfunk North German Public Broadcaster) surprised us with the news that the cop drama TATORT: SCHATTENLEBEN, currently being filmed in northern Germany, is particularly diverse, both in front of and behind the camera. For example, 17 percent of those involved are BIPoC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color), and 65 percent of the head positions are held by women. NDR and the production company Wüste Medien GmbH are using the so-called Inclusion Rider for the first time. The initiative came from director Mia Spengler. The goal of the concept, which originated in Hollywood, is to have as diverse a staff and cast as possible.

“NDR has been focusing on diversity in front of the camera for many years. We believe in diversity as a whole,” says head of television film Christian Granderath in the aforementioned press release mentioned. Unfortunately, that doesn’t apply to NDR’s prime-time cop dramas and thrillers of recent years, at least not when it comes to gender equality. Neither in front of nor behind the camera.

I analyzed the share of women for the six departments directing, screenwriting, camera, sound, editing and music of four television series with 90-minute films from the prime-time program: NORD BEI NORDWEST, the USEDOM CRIME STORIES, the NDR TATORTE and the NDR POLIZEIRUF 110.The period under investigation is 2017 to 2020.Two major studies by the FFA German Federal Film Board and public Broadcasters ARD and ZDF (“Gender und Film” and “Gender und Fernsehfilm”) were published at the beginning of 2017. By then, it should have become clear to the industry that there is a considerable gender imbalance in front of and behind the camera and that there is an urgent need for action.

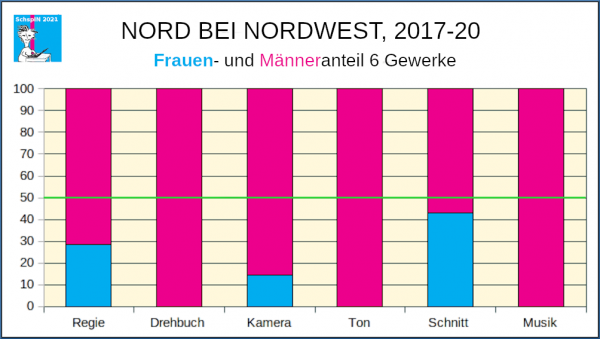

The series NORD BEI NORDWEST has been on air since 2014.There were nine films from 2017 to 2020. The following figure shows the percentage of men in pink and the percentage of women in light blue:

There have been two women directors in this format – Dagmar Seume (ESTONIA, 2017) and Nina Wolfrum (EIN KILLER UND EIN HALBER, 2020). Female editors worked in a third of the films. There has never been a female sound mixer or a female composer in this format. The music has always been composed by Stefan Hansen. The most hired sound mixer is Dutch Marteen van de Voort, who worked in this position seven times in 2017-20 alone. Eeva Fleig was the only female cinematographer (WAIDMANNSHEIL, 2018). All scripts for this format were written by Niels Holle and even more frequently by Holger Karsten Schmidt, who also developed the format. So we cannot really speak of a significant participation of women in the creative positions.

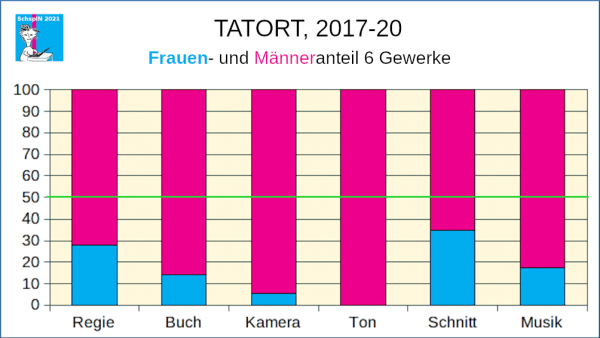

Not quite as bad but far from acceptable is the situation with the TATORTs (Crime Scene – Germany‘s Top cop drama). NDR is responsible for four: Hanover / Göttingen since 2002 and 2019 with Maria Furtwängler and Florence Kasumba (since 2019), Kiel since 2003 with Axel Milberg and Maren Eggert (2003-10), Sibel Kekilli (2011-17) and Almila Bagriacik (since 2018), Hamburg since 2013 with Til Schweiger and Fahri Yardim, and finally Northern Germany since 2013 with Wotan Wilke Möhring and Petra Schmidt-Schaller (until 2015) and Franziska Weisz (since 2016).

No pilot episode was written by a woman, which means that the cops, the main staff, the mood and the setting were created or specified by men. Of the 18 NDR TATORTs first broadcast in 2017 to 2020, none was written by a woman. There were only four scripts in which female authors were involved in teams. The proportions of women for screenwriting, directing and cinematography are 3-4% higher than those for all 145 German TATORTs in the same period, but still well below the respective proportions of women at film schools, i.e. the working potential in these areas. The biggest difference between the NDR TATORTs and all TATORTs in 2017-20 was in the editing department: the NDR female share is 35%, while that for all TATORTs is 65.9%.

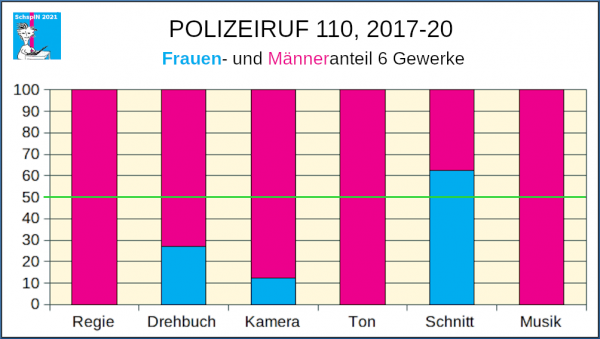

The only NDR POLIZEIRUF 110 is the one in Rostock, with Charly Hübner and Anneke Kim Sarnau. It was developed by Eoin Moore, its first episode ran in 2010.

None of the eight episodes from 2017-20 had a woman as director, composer or sound editor (Thorsten Schröder did that every time). One script was written by a female writer, Susanne Schneider (ANGST HEILIGT DIE MITTEL, 2017), two other women were in writing teams, Anika Wangard with Eoin Moore (FÜR JANINA, 2018), and Christina Sothmann with Lars Jessen (KINDESWOHL, 2019). Thus, at 27.3%, the proportion of women in this department is almost twice as high as in the NDR TATORTs.

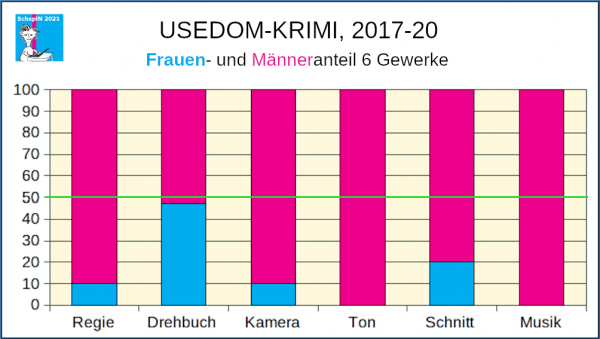

The fourth series, the USEDOM CRIME STORIES, is the only one developed with female participation. The first episode in 2014 was written by Scarlett Kleint, Alfred Roesler-Kleint and Michael Ilner (from 2015 as Michael Verschinin). 2017 to 2020 saw the creation of four 90-minute stories written only by women authors, three by Marija Erceg and one by Dagmar Gabler. In addition, there were five scripts by mixed teams. Only one was written without women’s participation (SCHMERZGRENZE 2020, by Michael Verschinin). All in all, this makes a female share of 47.4 % in the script department.

The only composer of this series is Colin Towns, there were several male sound mixers. Maris Pfeiffer is the only female director in this format (PAIN FRONTIER, 2020). I find it unfortunate and also not quite understandable why none of the USEDOM CRIME STORIES written by women were directed by a woman, and that only once was there a female cinematographer, the US-American Leah Striker on DREAMS (2019).

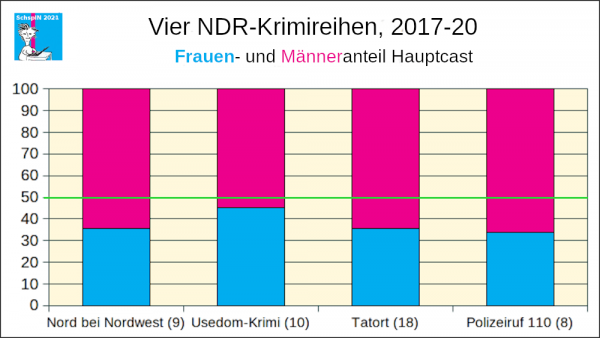

The next diagram shows the share of women and men in the main casts, i.e. the roles and actors published on the ARD website. Three formats have a good third of female roles, only USEDOM CRIME STORIES reach 45%. A higher proportion of women means more female character diversity and also a greater possible diversity of these roles, which is a basic prerequisite for a more realistic portrayal of our society and is therefore absolutely necessary.

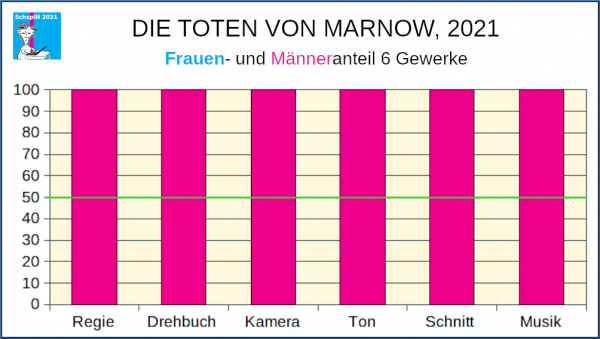

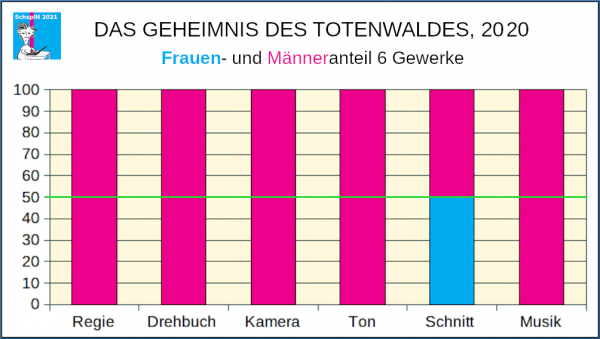

In 2020 and 2021, two television crime mini-series were broadcast on NDR: DAS GEHEIMNIS DES TOTENWALDES (2020), three times 90 min or six times 45 min respectively, and DIE TOTEN VON MARNOW (2021, funded by nordmedia), 8 episodes of 45 min each, broadcast as double episodes. These mini-series are not really comparable with the other four series, as they each tell one case only and are not self-contained stories in each episode. Also, in this respect, it is understandable that there were no changes in the team.

What is less comprehensible is why there are no women. The six pink columns of DIE TOTEN VON MARNOW speak a clear language, and only Julia Karg and Kai Minierski as an editorial duo spare DAS GEHEIMNIS DES TOTENWALDES a similar fate.

One is reminded of German TV series BABYLON BERLIN, where women being absent from the main departments – with all its negative effects – was overlooked, ignored or deliberately wanted. Of course men can produce a crime series on their own, why not? The only question is whether public TV really should be like this in 2020 and 2021, especially if the broadcaster involved in this case, NDR, believes in “diversity as a whole”.

To illustrate why all-male crews are unfavourable let‘s look at a scene from DIE TOTEN VON MARNOW. Chief detective Lona Mendt (Petra Schmidt-Schaller) has just been brutally beaten up in her caravan by Bernd Peters (Jörg Schüttauf), she is lying on her stomach across a table. The perpetrator’s gaze falls on her buttocks, clad in thin shorts, which we see in close-up. Peters then decides to rape her as well. The fact that her body can be interpreted as triggering this is dangerous and serves ancient clichés long believed overcome, “Well, if she was dressed so provocatively…”. I don’t know how Holger Karsten Schmidt had written the scene in the original script, but the way the scene was filmed seems to have struck nobody as unpleasant, neither the director nor the cameraman nor the editor, it didn’t bother them or they wanted it just so.

What’s to be done?

How can the share of women in film departments be increased? Via an inclusion rider / a diversity clause, as was done for the NDR TATORT mentioned at the beginning. Filmfunding body Filmförderung Hamburg Schleswig-Holstein developed diversity checklists. These are used to check planned diversity in the script, i.e. in the plots and the roles, and in the film teams. The aim is to encourage applicants “to consciously deal with the issue of diversity and to critically examine their own actions”. Currently they are only obliged to answer the questionnaire. I don‘t know of any consequences if an applying film project has many ethnically diverse roles but almost no female characters, and if no people with disabilities and no people over 50 work behind the camera.

In terms of gender equality, my “2 out of 6” model, supported by the leverage of public funds, seems quite uncomplicated and effective.

The NDR could decide today that all production must involve a woman as head of at least two of the six mentioned departments. Otherwise the cooperation won‘t come through. Not three out of six, because the proportion of women in training in these six areas is not 50%. (According to the 2017 study “Gender and Television Film”, 51% women graduated in editing, 48% in screenwriting, 44% in directing, 25% in cinematography and 11% in sound). Just two departments. So nothing impossible is being asked, the threshold is quite low. Two mixed teams, e.g. a musical composers‘ team and a script team, that would be enough. Or a female director, a female cinematographer and an editor, because more than two trades are of course also possible. That the six crime series mentioned above can still improve a lot in this respect can also be seen from the fact that only one third of all 45 films meet this low threshold, i.e. have at least two departments with female participation. There is still a lot of room for improvement. All the more so if the broadcasters were to decide that at least three out of six trades must involve women for funding, three, as a small compensation for the decades without women.

Thoughts on the Inclusion Rider

An inclusion rider – or diversity clause” – is not so much a tool as a passage in the contract, a written declaration of intent or target that also works as leverage. It was developed by Dr. Stacy Smith of the Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism at the University of Southern California for the US film industry, and the way it was designed it would allow celebrities, e.g. an actor or director, to make their participation in the film project conditional on the production meeting certain diversity criteria.

The inclusion rider originally included the clause that at least one woman and one representative of a disadvantaged group should be invited to the application process for each of ten core departments. Mind you, this is not yet about actual employment.

When casting small, “third-class” roles, i.e. daily roles, the composition of the population should be taken into account and they should be cast with as much parity as possible. This makes sense but does not go far enough. Why only small roles?

Because good intentions are not enough, – as we have seen for years, not only in the film industry – it makes sense to focus on equal participation and diversity and to include them in contracts and guidelines. What the implementation of an inclusion rider calls for, however, is the allocation of filmmakers to categories. And that’s where the whole thing gets a bit problematic.

Diversity is more than ethnicity, it includes age, sexuality, body shape and appearance, disabilities, pregnancy, socio-economic background etc. How is a production company, an editor, supposed to know if cameraman ABC is gay or has a disability if this information is not made available? Should they add to their showreel that the images were filmed by someone whose ancestors came from Southern Europe, North Africa or East Asia? Why publicise a disability if it does not affect one’s work performance? Why out your sexual identity if you fear – justifiably or unjustifiably – that you will be less likely be employed or discriminated against on set, or simply considers it a private matter?

Do we want a production to ask for and collect this data from its potential employees – voluntarily? Would this lead to more diversity and less discrimination? These questions need to be discussed to ensure more diversity and equality in the film industry.